Volume 16 - Autumn 2003

The Silver Kelmscott Chaucer

by James Brockman, Bookbinder and Rod Kelly, Silversmith

Have nothing in your binding that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful - with apologies to William Morris.

The Works

of Geoffrey Chaucer - The Kelmscott Press 1896.

Bound 1998-2003 by James Brockman and Rod Kelly.

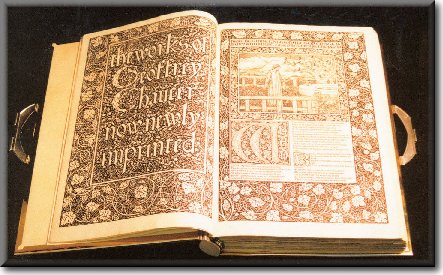

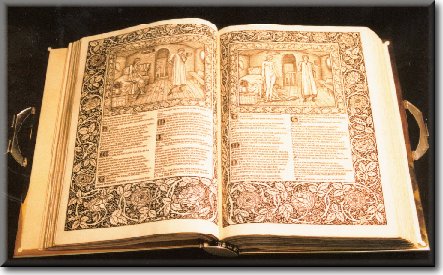

How do you compliment the finest achievements of Geoffrey Chaucer, William Morris and Sir Edward Burne-Jones in the twenty first century? Most bibliophiles declare that the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer finished on the 8th May 1896 at Morris' Kelmscott Press is the greatest book of the (almost) 20th century. There were a total of 425 copies printed on handmade paper and Rod Kelly, Silversmith and I were approached by John Keatley to bind one. John knew Rod Kelly having commissioned several silver items from him. He was also aware of my work, having purchased for The Keatley Trust at auction my first all metal single hinge binding, In Memoriam.

John owned a copy of the Kelmscott Chaucer which had been re-bound in a style he felt inappropriate. This then would make the perfect candidate for a new binding as the Collector's conscience would be clear, not having to remove the original published binding - an action considered worse than murder in the UK but completely acceptable in France!

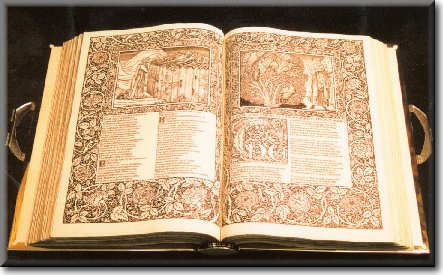

When John Keatley contacted me to ask if I would work with Rod Kelly on a silver binding for a Kelmscott Chaucer I was very interested. I had previously worked on several copies of the Chaucer including a vellum copy commissioned by Colin Franklin when I was running The Eddington Bindery in Hungerford in l975. This copy is now in The Southern Methodist University Library in Dallas, Texas. I knew the Chaucer was a heavy book with very narrow back margins and that it must open well to display the wonderful large printed borders. Normally "good opening" is achieved with flexible sewing and minimum spine linings but on heavy books like the Chaucer, the binder must compromise between flexibility and support of the spine.

|

Book open at Title Page |

|

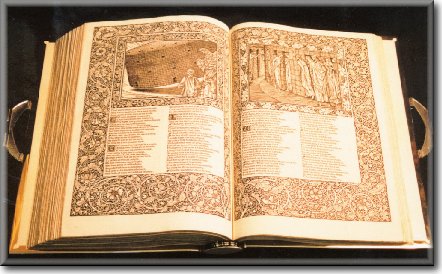

Book

quarter open

|

|

|

Book Half open |

|

Book

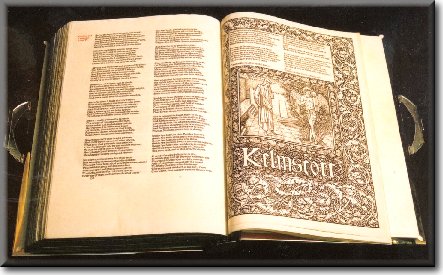

three quarters open

|

|

|

Book open at end |

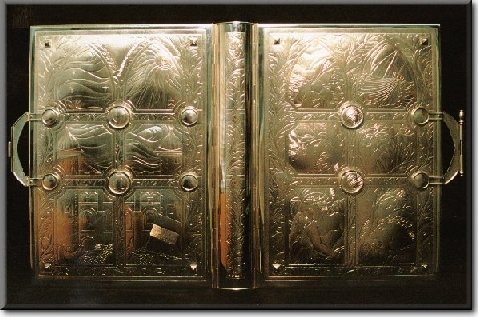

I knew immediately that I was only prepared to be involved with the binding if the structure was to be all-metal. I have frequently been disappointed by historical metal bindings that are compromised by using leather or fabric for the joints. Equally bindings with a single metal hinge at each joint will not open more than approximately 170 degrees unless the hinge tubes stand above the joint which is not acceptable for fine work.

The answer to these two problems of a metal hinge and a supported but flexible spine lay in my early experimental work with book structures. Twice in the past I have used a double hinge on each joint to allow perfect opening. The first time was in 1978 on my binding New Directions in Bookbinding and again in 1979 on Beauty and Deformity. The double hinge made of metal is virtually indestructible and allows the covers to open fully without pulling back the text block. On both these earlier bindings I used the double hinge with a flat spine which threw up when the text block was opened. These earlier experiments had led me on to my single hinge bindings, the first being In Memoriam in 1984, The single hinge binding automatically created the concave spine which led me to produce my first rigid concave spine binding in 1993 The Doves Bindery (now in the British Library Collection).(1) Therefore the solution to the structural problems presented by a full silver binding on a heavy large book with narrow back margins was obvious - the first rigid concave spine binding with a double hinge at each joint.

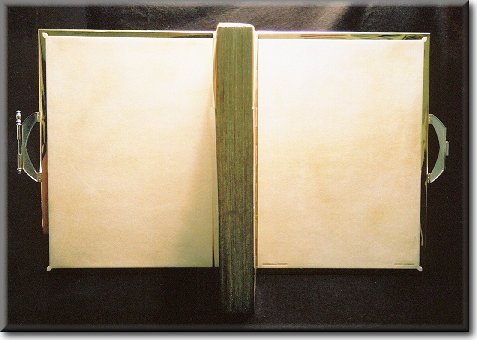

It was not so easy to convince all concerned. John Keatley, after much consideration, agreed with the concave spine so long as it wasn't too obvious. He suggested a dummy convex spine to make the binding look more conventional. I wanted the honesty of the concave spine but understood his reservations and admit that the finished binding looks very comfortable with its convex spine. Rod Kelly is a wonderful silversmith but he thought the double hinges were far too complex and argued for some time that a single hinge on each cover would be fine - this was the closest I got to withdrawing from the project. Rod and I had an excellent relationship throughout but the complexities of a binding structure are often alien to book people let alone a silversmith with no previous bookbinding experience!

Whenever these misunderstandings over structure occurred, I made a brass model of the part in question to demonstrate the function. To Rod's credit once the details were proved to work, the objections melted away.

I started work on the book with the help of my assistants Simon Haigh and Diane Walder in December 1998. The book was taken down, there were many tissue repairs that needed re-doing and the book was dry cleaned throughout. A folio of toned vellum was added at each end and the edges were gilt on the deckle. Rod Kelly made up five curved stainless steel sewing supports. These had stainless steel countersunk screws soldered to them for eventual fixing of the cover to the text block. The sewing supports were covered in acid-free paper and the book was sewn with the concave spine being formed as the sewing progressed. It was quite tricky controlling the swell, when sewing, to ensure that the text block thickness matched exactly the length of the stainless steel sewing supports. The book had to be sewn twice to achieve this. After sewing, double endbands in black, grey, white, and gold threads were sewn on and the spine lined with cotton and 12 linings of acid-free paper between the stainless steel sewing supports.

In order that Rod Kelly could continue with the silver cover, I made a wooden block to the exact dimensions of the sewn text block. This enabled him to construct the cover without risking any damage to the book.

Rod was entirely responsible for the decoration of the cover. John Keatley had conceived the binding as a memorial to his mother and Rod was asked to incorporate imagery that related to the Keatley family as well as to the Burne-Jones images in the book.

Toned

vellum Doublures and Fly-leaves

Toned

vellum Doublures and Fly-leaves

I discussed with Rod the traditional ways of dividing the book cover based on raised bands, placing of bosses and relating the clasp position to the decoration. He took some of this on board. He decorated the silver sheet by chasing.(2) This involved embossing the silver with steel punches and a repousse hammer. The silver is worked over warm Swedish pitch for support and the images are raised in a low relief style that is most successful, it reminds me of the cushioned boards on a leather binding.(3) It took Rod approximately one hour to complete one square inch of chasing. The extensive chasing caused the silver to warp and Rod enlisted the help of a friend, Ian Calvert, to help him undertake the heart stopping procedure of bolting the decorated covers to stainless steel plates and heating them until they glowed red hot. This relaxed the tensions from the silver caused by the chasing and to everyone's tremendous relief, the covers stayed flat.

After many telephone calls, letters, visits to my bindery in Oxfordshire and Rod's workshop in Norfolk, the binding was ready to assemble. I drove to Norfolk with the sewn book and we constructed the cover around the text block. I returned to Wheatley to add the toned vellum doublures, stainless steel hinge stops and to sign the book in gold on the rear doublure. I had decided early on that any silver that came into contact with the paper leaves or vellum doublures should be gold plated to avoid any problems with the silver tarnishing and causing staining. As a result of this decision there is a wonderful reflection of the gilt edges in the gold plated squares.

Rod spent in excess of 400 hours on the silver work. My work on the binding was completed in March 2003 - 4 years and 4 months from beginning to end and amounted to 220 hours.

James Brockman - was an apprenticed finisher in Oxford from 1962-68. From 1968-73 he worked with the late Sydney Cockerell at Cambridge. He started and managed The Eddington Bindery 1973-76 and started his own workshop 1976. He was President of Designer bookbinders from 1985-87. He has also lectured and demonstrated extensively in Europe, U.S.A., Canada and Australia. He currently holds the position of President of the Society of Bookbinders.

Endnotes

(1) The Rigid Concave Spine - Time to throw away your Backing Hammer, an article by James Brockman fully explaining the ideas and methods of the Concave Spine, was published in 'Skin Deep', Volume 2, August 1996.

(2) Chasing is a decorative process to obtain a relief of surfaces by delicate tracery, low relief or embossing. Chasing can include a variety of methods: Embossing Working from the back of the surface to obtain depression on the surface of the material. This method does not create definable or sharp marks or lines. Repoussé (pushed back again) work, follows the lines and shapes created by embossing and is used to sharpen the lines and marks on the front of the work.

(3) Swedish Pine Pitch offers a firm but yielding surface in which to hammer the sheet of metal against and because the pitch is sticky, it will grip the object while the chasing work is being carried out.