Volume 26 - Autumn 2008

Extreme Bookbinding - A fascinating Preservation Project in Ethiopia.

by Lester Capon

It began with 8a telephone call one Thursday morning in May 2006 from James Brockman. The conversation went something like this :- J.B. - "Do you want to work in the Ethiopian mountains on a 6th. century manuscript?" L.C. - " Yes" When, some months later, I was being hoisted up a sheer rock face a stones throw from the Eritrean border, trusting my prolonged existence to an ancient leather strap and an even more ancient monk, coupled with my laughable attempts at rock climbing on the only day of rain in the whole trip, I had time as I dangled dangerously to reflect, through gritted teeth as it were, on my hasty reply.

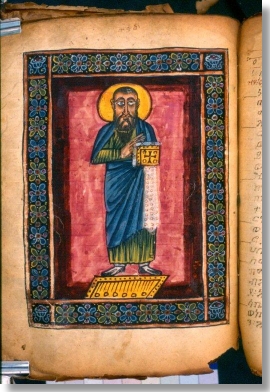

St Luke

Introduction

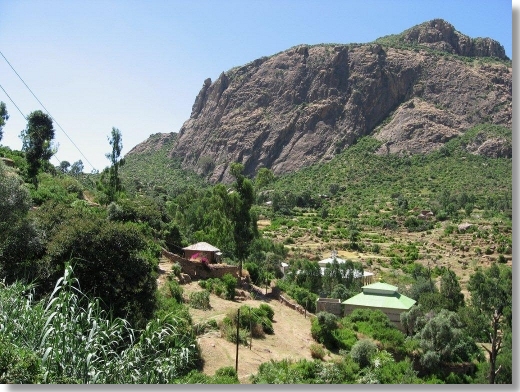

The two manuscript volumes are kept at the Monastery of Abuna Garima in the Tigray Region, that is the Ethiopian highlands, in the north of the country. There are many monasteries and rock-hewn churches scattered around this area in varying degrees of inaccessibility - up mountains, on lakes and miles from anywhere.

They nearly all have 'treasures - crosses, crowns, manuscripts and books' which are shown, though not always, to the few visitors who pass through. It is not uncommon to trek for a day over rough mountainous terrain to reach one of these churches, only to find that the resident monk is disinclined to show its treasures, or that he is simply absent, or, dare I say, sleeping off a home brew tasting session.

Perhaps the most famous one is at Lalibela. This is a group of churches situated in the Lasta Mountains, Northern Ethiopia, which are carved out of, and freed from, the rocks, creating a space around them. They contain striking carvings, friezes and frescoes as well as manuscripts.

Of all the manuscripts in Ethiopia the gospels at Garima are believed to be the oldest and have been dated by European scholars to the sixth century. (They are believed by the Coptic monks there to have been written and illustrated by Abba Garima, their founder and one of the evangelising saints of Ethiopia, in one day!) There are plenty of wild beliefs, I guess, in all cultures. Gabra Manfas Qeddus, born in Egypt, was supposed to have lived for 562 years, neither drinking water nor eating food.

The Charity for the Preservation of Ethiopian Heritage in London were organising this project. They had been advised of the options and viability of any work being carried out. Clearly, the ideal treatment for these manuscripts would have been removal to a conservation unit where it could be analysed, taken apart, repaired and reassembled. This of course would be a huge undertaking - years of work - a massive commitment from an institution or team of conservators. In practice this will never happen - the books rarely see the light of day, and are not even allowed beyond the perimeter of the monastery's Treasure House courtyard. They have never left the monastery in over 1400 years, let alone the country.

I agreed with the sponsors that a limited amount of consolidation and repair could be achieved without compromising the volumes and that this would result in the manuscripts being safer to handle.

Accompanying me for some of the time would be Jacques Mercier, an expert on Ethiopian manuscripts, icons, healing scrolls and botany, who has spent about thirty years on and off in Ethiopia and was, thankfully, more than capable of dealing with the complicated hierarchy and bureaucracy there and Daniel SeifeMikael, his assistant, an Ethiopian lecturer in Theology who was kindness personified. I was lucky that Mark Winstanley, owner of the Wyvern Bindery in London volunteered his services as assistant. He was unfailingly helpful with all the work, very jolly company and excellent at keeping the monks amused and occupied. (This last skill was very necessary, as we shall see.)

Preamble

The monastery itself is a group of small stone built huts some circular, some square with turf roofs where the monks live. There is a church, gaily painted on the outside in reds, greens and yellows; having small windows, its interior is dark and atmospheric.

Part

of the monastery church

Part

of the monastery church

This was usually locked shut although occasionally a monk could be heard within reading aloud from the gospels - using not the early manuscript but one of the many other later manuscripts they have, bound in wooden boards with heavy leather outer covering and fabric inner lining, substantially hidden by the large turn-ins. They usually have illustrations at the beginning of St. Giorgis, their patron saint (our own man, the very same) slaying a dragon, and the Virgin Mary with Jesus at the end. I believe it is quite a common practice to have the illustrations 'freshened up' every so often.

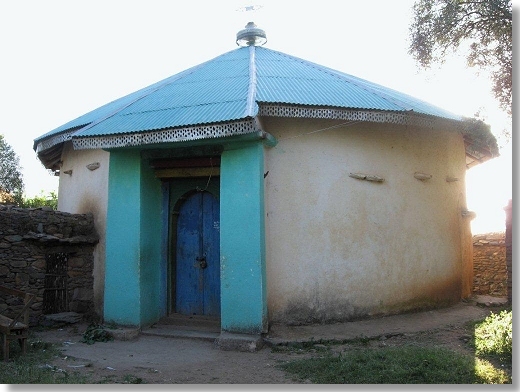

Near to the church was the Treasure House, a charming circular blue painted building. This also was often locked. It housed not only the manuscripts but also, in a huge glass fronted cabinet, dozens of books, old and new, made in the same Coptic style of binding. There were seventeenth and eighteenth century ornate crowns, a fourteenth century ceremonial silver spoon, early silver crosses, robes and fabrics, silver and pewter jugs and trays, faded curling photographs all crammed together. On the floor were faded and flea infested rugs.

Hanging everywhere were the bright multi-coloured umbrellas they use as sun protection, each section a different fabric, and wonderful book bags of very tough leather and vellum. Mahda, I believe they are called. I will never forget my first entry into this dark and magical room as, watched intently by the Keeper of the Treasures, I sat on a stone seat built out from the wall and let my eyes grow accustomed to the dim light that gradually revealed all these wondrous objects.

Treasure

House where bible is kept

Treasure

House where bible is kept

But I am ahead of myself.... We arrived at Addis Ababa and took an internal flight over the Simeon Mountains to Aksum. Here we discovered that half of Mark's luggage had stayed with the plane and was on its way to Gonder. Well, it could have been worse - it could have been my luggage. We were driven to Adwa, the nearest town to the monastery. The scenery was stupendous - a mixture of mountains and grasslands and Acacia and Olive trees with some cultivated areas. According to Sidney Cockerel many of the boards used for bindings are of Olive wood.

The main crop is Tef, a sort of wheat, with which they make their staple diet of injera. This grew everywhere, greeny gold, blowing in the breeze like our fields of wheat. So much more attractive than what it eventually produces. Injera is basically an edible plate - spicy meats are placed on it and the injera, which has the look of an old damp grey kitchen rag, is broken off in order to pick up the meat. A good sociable system but I fear I never adapted to the taste and consistency.

On our first day at Adwa it was the Festival of Abuna Garima so there was no chance of getting over to the monastery. The monastery, however, had come to Adwa. Dozens of monks looking splendid and imposing in robes and crowns, carrying huge crosses and books, were in a procession through the town, gathering as they went half the inhabitants, plus three Europeans - or faranji -Jacques, Mark and me.

We arrived at a hill top church and watched with the large, noisy and excited crowd the monks dancing and singing, with groups of women complementing the extraordinary sounds with continuous ululations. We were told by locals, with pride and pleasure that the old church had been torn down, and replaced with this one, with brand new murals.

This was a rich and colourful event that continued the next day. The Patriarch, or Pope, of Ethiopia was in town. He had originally come from the Garima monastery, and was visiting Adwa to speak to the masses, which he did at length. To the monk's disappointment and annoyance he did not visit the monastery and the last we saw of him was as he was driven away, throwing handfuls of tiny crosses, like sweets, out of the window, to enthusiastic children chasing the car. As absorbing and thrilling as it was it did mean that two days had gone by and I hadn't even seen the monastery, let alone the manuscript.

Procession

preparation

Procession

preparation

The next day came and still we were told it was not possible to go there. Daniel was working hard waving the necessary documentation in front of the necessary noses and I think it was a frustrating and dispiriting experience for him.

Finally that Wednesday afternoon we were driven in an ancient Toyota van by the normal team of three - one to drive, one to take the money and one to open the sliding door - along the rocky road up into the hills to Abuna Garima. We were greeted with a sort of nervous and wary friendliness.

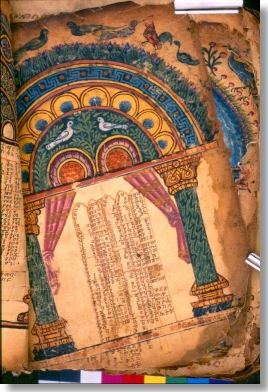

After some discussion - I say some discussion, - it was about 3 hours of talking. Mark and I took the time to climb the slopes above the monastery and gained a terrific view of the surrounding valley standing on the holy spot where Abba Garima spat on the ground and created a permanent spring - the manuscript was produced and I had my first breathtaking sighting of the beautifully bright colours of the illuminated pages which were at the beginning of each volume, although some were loose. I'd seen photos previously in London when I was preparing for this work - but seeing this book in real life was truly astonishing.

It was big - you could fell an ox with it, it was beautiful - the colours were vibrant - and it had, as I said to Mark at the time, the look of a burst mattress. The text pages were written in Ge-eze, the earlier language spoken in this area, but no longer in use. They speak Tigrinya now in this region.

The monks even at this stage were still undecided about how to proceed. The problem was that although they are the custodians of the books, the ownership rests with His Holiness, the Patriarch. The hierarchy of the various diocese also felt it necessary to give their permission. This was further complicated by the fact that the Ministry of Culture maintained that the government owned these types of artefacts and only they could give permission. We were pawns in the political power struggle between Church and State, as were the monks. I felt sorry for the Abbot who kept peering at all our letters of authenticity in a manner that suggested that he couldn't actually read.

Part

of the monastery

Part

of the monastery

Eventually we left - the monks were to have another meeting that evening, and we were to return the next morning.

The next day, we were allowed to start. I took out the materials I had brought and explained with the help of Daniel that these were the finest skins of vellum and the best papers from Japan.

The books were brought out into the courtyard of the Treasure House which was to be my 'bindery'. Not ideal, we had to move the benches (which consisted of an old table and two funeral biers) twice daily to avoid the sun whilst also contending with a gentle breeze. Other slight differences between this work space and my workshop at home included the occasional visits of donkeys and the regular visits of monkeys. I kept an eye on them as I was fearful that one may jump down from the roof, grab a folio, scrunch it up and run off down the hill.

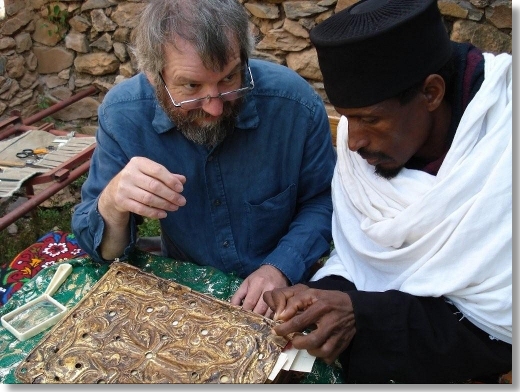

At the start of work nearly all the monks gathered round, eyes fixed on me, Jacques started photographing from all angles and the Abbot sat down close next to me. Of course at this moment I wished them all elsewhere. Mark did his best to distract them. He did this brilliantly on many occasions as the monks were constantly wanting to sit virtually in our laps watching us work. He would engage them in conversation, even though they knew no English and we had about five words of Tigrinya, he taught them to ride a bike, which he had hired for a few days, he showed them how to burn their hands with the sun and my magnifying glass, and generally entertained them.

On this first occasion, however, there was nothing for it but to proceed with dozens of eyes following my every move. Having taken some initial photographs I picked up my 2B pencil to lightly collate the folios that were to be removed. I was alarmed to have my hand stopped by the Abbot. He did not want me to add anything to the great man's work. However, after a while he started to relax and to my amazement and even more alarm picked up one of my scalpels and started trying to cut some of the threads. My turn to stop his hand.

Unwanted

assistance from the Abbott

Unwanted

assistance from the Abbott

Gradually we settled into a routine of Mark and I working as a team. There were always at least 2 or 3 monks lingering casually as close as they could get, occasionally trying to examine the verso of the page we happened to be on. I called them neh nehs the name of a type of Hawaian goose - the name translates as - lets sit around and chat.

We arranged our makeshift benches - the funeral biers - as much as possible keeping them back. One morning one of the biers was missing - it was in use in the nearby village. Like the flies that continually pestered us, they had to be swotted. I did not blame them for this close interest. They made it clear they were grateful for the work. This work, in the most extraordinary circumstances and situation, Mark and I undertook in the most professional and responsible manner we could.

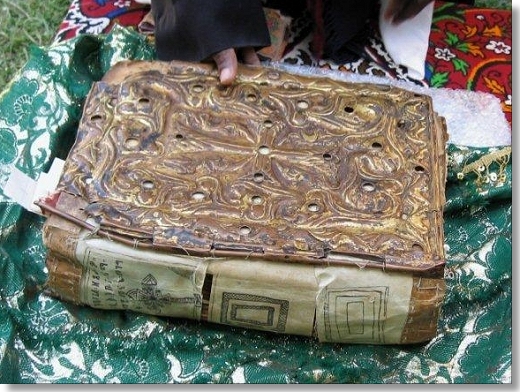

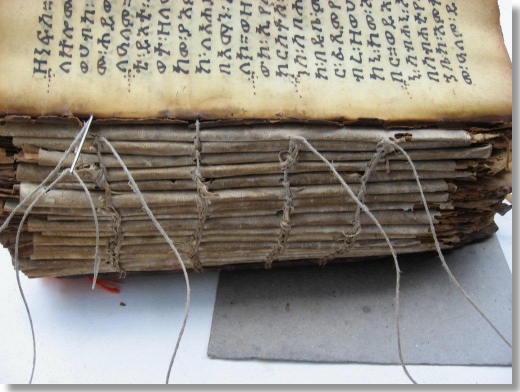

Condition and Treatment The Abba Garima Gospels are three manuscripts bound into two volumes. The first (AG1) contains the sixth century manuscript. The second volume (AG2) also contains the sixth century manuscript which is bound together with a later manuscript, from the 14th. Century.

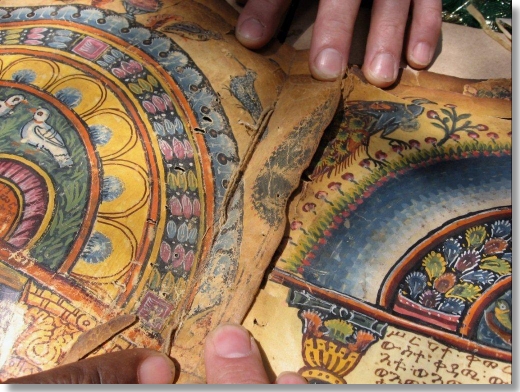

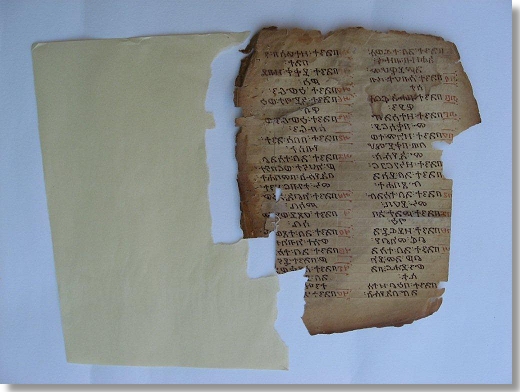

AG1 is sewn with two pairs of sewing stations with a hard 2 ply linen thread. The boards are copper with holes that would presumably have displayed coloured glass or jewels originally. On the inside of the back cover are the remains of a deteriorated papyrus board. The metal boards are attached loosely by the sewing threads from the sections, as well as from the tacketing at head and tail, being wrapped around the hinge rod. The spine is three separate pieces of much more recent vellum, brought round under the boards and sewn through the preliminary pages approximately four cms. from the back fold, with parchment strips. This prevented satisfactory opening of these pages. Further damage had been effected by vellum guards being sewn into the pages, with parchment strips, diagonally through the images, thus preventing proper opening, and the formation of creases where attempts had been made to fold the vellum leaves back. With this secondary sewing, intermingled in places with a tertiary sewing of a soft 2 ply linen thread from some later repair, the most important and attractive folios were rendered inaccessible and vulnerable. On one occasion the page was creased in two places and sewn through the doubled part. All four edges of each page had damage and missing areas through use over fourteen centuries. Insect damage was found throughout the main text block.

|

Old

repairs through folded Image

|

|

|

AG1 - Front board and spine |

|

AG2

- Front board and spine

|

|

|

Restricted opening from previous repair |

|

Profiled

Taizan Paper

|

|

|

Reattaching Front Board on AG1 |

|

Repaired

Sewing on AG2

|

|

AG2 is also sewn with two pairs of sewing stations with linen thread. The wooden boards are covered in a chased metal of a later date than AG1. The spine edges of the wood are chamfered. There are no holes horizontally through the boards (in keeping with later Coptic bindings) but there are many holes vertically through the boards suggesting later additions for repair purposes.

The illuminated and text folios in AG2 had suffered the same treatment as in AG1, and were in a similar condition.

Of the illuminated folios in AG1, three had to be moved to their correct place which was in AG2; two had to be moved to their correct place within AG1 and three had to be reversed, having been sewn in along the foredge.

Of the illuminated folios in AG2, three were loose and needed to be reinserted, and one needed to be moved to its correct position.

There was one extant double folio in each volume. The vulnerable edges of the illuminated folios were to be repaired where possible to prevent further damage.

The illuminated pages needed to open more freely. With all the added repairs the main advantage of Coptic binding - the ability to open the book completely flat - had disappeared.

AG1

The front board was removed by untying threads that were wrapped around the hinge rod. The spine vellum pieces, which were sewn into the first pages, were unthreaded where possible, releasing them, and creating access to the spine folds. The first twelve pages - illuminations and text - were detached and the repairs running across some of the pages were unthreaded.

The torn and damaged edges were repaired in small areas with laminations of Taizan 36gsm smooth toned Japanese paper using a parchment size adhesive.

I had taken with me a variety of Japanese papers - different weights, tones, textures, and a selection of differing thicknesses and tones of vellum. Although I had seen photographs of some pages it was difficult to be sure which material would be most suitable until I actually confronted the manuscript. The Taizan was a sympathetic match.

It would have been inappropriate to build up the large missing areas with new vellum as the stresses created would have transferred through to the original vellum causing more possible damage. Also the new pieces of vellum would have been largely unsupported by the rest of the volume and would therefore be vulnerable to damage, again possibly transferring through to the original. The torn edges and small vulnerable areas were consolidated with the toned Japanese paper.

Two laminations of Taizan paper were profiled to the spine edge shape of each single folio, edge pared and attached to the vellum page. No single folios were guarded together to create a double folio, the validity of which I could not be certain of.

A loose vellum guard was added around the outside of the spine folds to strengthen and support the sewing.

The loose text pages were repaired similarly and reassembled in their correct order. New sewing hemp cord was connected into the existing sewing of the text block, and the newly arranged and repaired folios were sewn in using the normal Coptic sewing method which had been employed throughout the rest of the book.

A blank, toned vellum flyleaf was sewn in to protect the first page from the inside of the copper board.

The three later vellum spine pieces were sewn into the stub of the new flyleaf enabling freer opening, and not hindering the opening of the first few pages.

The front board was reattached using the threads from the sewing which were wrapped and tied around the hinge rod securely.

Before I go on with describing the second volume work I should interrupt myself by mentioning that we were interrupted in the second week by a visit from the Mr. Fissela Zibola from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism looking very fierce, and telling us in no uncertain terms that we did not have permission to be working on the manuscript. We should stop immediately and return to Adwa with him. We proffered a letter that Jacques had left with us. Jacques and Daniel had left us several days before to oversee the conservation of an icon in another monastery several hundred miles away. Mr Zibola and Jacques obviously had some history. . He wasn't impressed and we had to leave the book - pages loose - and we were driven back. If we could not prove we were legitimately working we were told it was prison for us. Fortunately Jacques sorted this out and we had quite a pleasant afternoon being treated to some sort of coffee ritual at the hotel.

Anyway to return to the book.

AG2

The early part of the manuscript was separated from the later part. The illuminated folios were treated as AG1. Again there was only one extant double folio. The existing sewing was pretty shaky so it was strengthened with new hemp cord being sewn in, using the original sewing stations, and the newly arranged and repaired folios were added. A new toned vellum flyleaf was sewn in for protection against the board. The early manuscript was at the back of this volume so the front board was detached and sewn onto the front of the early part using existing attachment holes in the wood.

By returning the sewing to its original structure the illuminated pages could be viewed completely and with no real strain on the vellum. No evidence has been destroyed of what has happened to the books over the centuries - the holes from the misguided repairs using the parchment strips are still there, and samples of those strips and other sewing materials have been retained. Extensive amounts of debris - dust, leaves, insects etc. were found in the back folds of all the sections throughout the book. These were left in situ, partly as evidence for some possible future study and also9 because the removal would further loosen the sewing.

The pigment of the images was not flaking, and the vellum of the illuminated folios, despite being worn away in areas, was sound and more robust than the vellum of the text folios. It had also aged differently by becoming darker and more greasy. It may be that these pages were produced elsewhere, possibly in Egypt, and brought into Ethiopia. The differing appearance may simply be due to the more constant handling of these pages.

When the work was completed the monks were generous in their appreciation. We had decided to take them gifts, and noticing that they only had 2 drinking glasses for their tea - they had plenty of large cups for their home made beer - we bought a set of twelve. This was fortuitous as they looked on them as symbolic for the 12 Apostles. Jacques had suggested a more dramatic gift - a sheep for a feast. We got our taxi chaps to buy one which they brought out on the last evening. Mark presented the glasses and some other items showing great defference to the Abbot which surprised and pleased them. A small ceremony of thanksgiving for the work took place in the courtyard. Mark and I and all our families were blessed. Prayers were offered, counted out by the Abbot on his finger joints - as a Catholic will do on his rosary.

The books were returned to the wooden chest that had previously been made to house it. I understand it may be made more accessible to travellers - not for handling, but for viewing - bringing in some much needed funds.

Although I have worked on many early manuscripts this is by far the oldest and I felt privileged to be temporarily a part of this unchanging culture of poor and dignified Coptic monks. Repairing old books, I always feel I am touching history. With this book it was ancient history.

Postscript

I mentioned being suspended by a leather strap at the beginning of this article. This occurred on a trip out (we couldn't work on Sundays) to visit Debre Damo, an important early monastery , founded in 4th. Century by Arigawa, one of the main 9 saints, about 100 miles from where we were. Miraculously, considering the terrain and the condition of our vehicle, skilfully driven up and down rocky steep slopes and through rivers by our cheerful team of chauffeurs we reached this distant site. One of the local boys came up to me as I walked from the van and said solemnly ' You are a very old man and I will help you'. Nonplussed, I gratefully handed him my knapsack to carry.

The monastery is on a plateau reached only by scaling a sheer cliff face. The arrangement is that, being secured by the strap from the top, one climbs up the face of the cliff utilising another rope. Mark shinned up first, making it look easy.

For the whole three weeks that I was in the fabulous country of Ethiopia I had a nasty debilitating chest infection which I somehow picked up just before leaving England. I did feel at my lowest ebb that day, in the pouring rain, at the foot of the cliff. I really wanted to see the monastery with its books and ceiling carvings so it had to be done. I struggled up but was of little help to the monk holding onto the strap. When, with one final effort, he hoisted me over the top edge I looked up into his kindly grinning face to see that he must have been at least eighty. Feeling, and I'm sure, looking foolish (Mark has a photo) I recovered enough to enjoy this remote religious site where the monks are self sufficient, even having their own livestock and reservoirs of water hewn into the rock . The trip down was, as I suspected, just as vertical and I was accompanied by many whoops of encouragement.

I would like to thank Jacques Mercier, Daniel SeifeMikael and Mark Winstanley for all their much needed help and support. Also thanks to Tova Irving at William Cowleys who was extremely helpful with suggestions regarding the vellum.

Lester at Work

Lester Capon trained at Camberwell School of Art and Crafts from 1975 - 1977. He trained with and worked for James Brockman from 1977 - 1993. This involved working on a wide range of books, repairing manuscripts and early printed books and fine binding and presentation boxes. From 1993 - 2000 he was Programme Manager for the Fine Binding and Conservation course at Guildford College. Since 2000 he has worked as a self- employed bookbinder in Tewkesbury; He was elected a Fellow of Designer Bookbinders in1986 and was President from 2003 - 2005. Collections include - British Library, HRHRC Texas, John Rylands University Library Manchester, Liverpool Library, private collections in U.K. and abroad.